Learning was fun with Madame Slack and Monsieur Patapouf

An educational television service for teachers, by teachers

By George Kirkland, BSc, ARPS

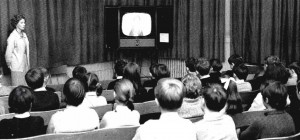

The name “Glasgow Educational Television Service” is unlikely to be familiar to most of you unless you went to primary or secondary school in Glasgow in the late 1960s or early 1970s. If you were in primary school then, it may remind you of sitting cross-legged in the school assembly or dining hall watching a large black and white television set on a wheeled stand. You will probably think of TV programmes called “Beginning French” helping you to learn spoken French, presented by Madame Slack, assisted by Monsieur Patapouf (I believe it is colloquial French for an overweight person) and a dog called Cliquot. Learners were encouraged to “Ecoutez et Repondez” (Listen and Reply) by Madame with the class teacher hovering on the fringe of the class, checking and correcting individual intonation. Before the programmes started in 1965, only 24 Glasgow primary schools had organised French lessons. Within a very short time, all 212 primary schools had French in their curriculum. If you were in secondary school at that time, then learning Maths by television is likely to figure in your reminiscences of school days, with programmes about algebra, geometry and other maths topics transmitted daily.

The ETV Service started TV transmissions by cable to schools on 30th August 1965, the beginning of the new school session. It was the first closed circuit television (CCTV) network of its kind in Europe. Just 5 years later in 1970, Glasgow had the largest closed circuit schools ETV system in the world. The City Fathers unexpectedly had proved to be far sighted innovators.

The mid 1960s were challenging times for the education system for at least two key reasons. Firstly, the Russians had beaten the Americans to be the first in space, when Yuri Gagarin made the first orbit of the Earth on 12th April 1961 aboard the Vostok 1 spacecraft. One American reaction was to overhaul immediately and completely their school syllabi in Maths, Physics, Chemistry and Biology. These changes were quickly absorbed by the UK resulting in radical new syllabi in these subjects in Scottish schools. Teachers had to be retrained, supported and provided with new teaching materials. At the same time, the post-war baby boomers were working their way through schools leading to staffing shortages, especially in maths and the sciences. In 1963, Glasgow, with one fifth of the school population of Scotland, had a shortage of nearly 1100 certificated teachers (probably about 14% of the teaching workforce in Glasgow). There were about 30 primary classes, mainly in the east of the city, which could only be taught part-time. In addition, there were uncertificated teachers, possibly as many as 700, with little prospect of freeing much time for them to undertake in-service training.

From 1960 onwards, American ideas about using educational television to relay lessons or lectures from one part of a building to another by cable were diffusing across the Atlantic, helped by demonstrations and exhibitions of relatively cheap TV cameras and other equipment from manufacturers.

Taking all of these factors into account, Glasgow Education Committee launched a brave experiment. In April 1963, three live educational programmes, each lasting over an hour, were beamed by microwaves from Glasgow City Chambers to a school 5 miles away on the perimeter of the city. This proved so successful both in technical and pedagogic terms, that planning for a full scale system started.

A TV Centre was reconstructed in the building on 151 Bath Street formerly occupied by the School Health Service. (In the 1870s, this had been the home of Dr John Gibson Fleming MD, a Surgeon at Glasgow Royal Infirmary and a member of Glasgow University Council.) The Centre had space for 3 TV studios (although only one was initially constructed), meeting rooms, offices, technical and graphics areas. The total cost was £65,000 (equivalent to about £1.2M today).

Studio RCA VTR

The cameras, telecine, video tape recorder and ancillary studio equipment were all of broadcast standard, since the aim was to try to match the broadcasters’ technical and production standards so as not to disadvantage the programmes in the eyes of the pupils. There were 3 black and white TV cameras, two on wheeled tripods and one on a pedestal that allowed it also to move up and down. These and the associated engineering equipment were rented from Pye Televison Ltd., a Cambridge company. The selection of the video tape recorder (VTR) system was a problem. Broadcast machines cost about £30,000 each (about £500,000 today) and could not be afforded. Ones at the other end of the price range were unreliable. Eventually an RCA TR4 VTR was selected on a rental and maintenance basis. This used 2 inch wide magnetic tape running at 7.5 inches per second. The VTR was the size of a large wardrobe and consumed 29 miles of tape in its first year.

It was decided to use an underground cable system for distribution, since it was about the same cost as microwave links but could transmit more than one channel. A company called British Relay (BR) began work in October 1964, laying 100 miles of cable via the old tramway ducts to all primary and secondary schools. There were 18 repeater stations around the city to amplify the signal. Since Jordanhill College of Education and the University of Glasgow both had their own studios and a similar BR system to link those studios to their lecture theatres and other rooms, cable links were added from these facilities to ETV Centre in Bath Street so that they could also transmit programmes to schools, proving a very valuable facility for in-service training of teachers. The system was rented from BR over a 15 year timescale. Each primary school had 1 TV receiver and all secondary schools had 2.

By the end of April 1965, a staffing complement of 10 (only 3 of whom had previous experience of TV) had been recruited and inducted, led by the Director, William G. Beaton. Initial help in sound and lighting came from BBC and STV. Apart from those admin. and technical staff, it was decided that programme production staff (writers, presenters and producers) would be recruited from teaching staff in Glasgow and trained for their roles in Glasgow ETV. Scriptwriters and presenters were trained initially at the College of Dramatic Art (now the Scottish Conservatoire) which had a studio not unlike that at 155 Bath Street. Producers were trained on the job, rehearsing and recording programmes, reviewing them and repeating the process until the programme was judged satisfactory. With experience, this process became shorter.

ETV Director William Beaton outside the ETV Building

Willie Beaton had been appointed in 1964. He was a graduate in English from University of Glasgow and taught in Canada before getting an education degree from Toronto University. After teaching in Bellahouston Academy and 5 years in the Royal Navy during the war, he joined the Educational Film Association and Educational Films of Scotland as joint secretary. He was a fine and inspirational leader of his team, welding a group, largely inexperienced in the complexities of television, into an efficient production system in the relatively new area of educational television.

The Glasgow Educational Television Service was launched on 30th August 1965 at the beginning of the new school session. It was followed by similar systems in Plymouth in 1966, Inner London in 1968 and Hull in 1969, all benefitting from the pioneering work of Glasgow ETV. The official launch ceremony was held on 24th September 1965 in the City Chambers. In a live transmission from the studio in Bath Street, the Rt. Hon. Willie Ross MP, the Secretary of State for Scotland inaugurated the service followed by remarks from the Lord Provost, Sir Peter Meldrum. Sample excerpts from French and Maths programmes were then transmitted to the City Chambers whilst the official party travelled from the studio to join in the celebrations.

In its first year, the service produced 118 programmes on Maths, amounting to 642 transmissions, since each programme was repeated a number of times each week to overcome timetable constraints. There were 68 French programmes (773 transmissions) and 14 (44 transmissions) on Cuisinaire, a system of teaching arithmetic using coloured rods which had recently been introduced into primary schools. These latter programmes were transmitted at around 15.35 for in-service training of teachers. Following on at 16.30 was a preview of the Maths programme to be transmitted on that day the following week, so that teachers could stay ahead of the transmissions. The annual budget for that first year of operation was £77,000 (equivalent to around £1.4M today). That included salaries, cable and equipment rental and maintenance and building maintenance.

Since there was only one VTR, it had to be used for transmission until about 17.00, when it was used to record studio output as new programmes were rehearsed and put on tape. Primary French programmes were recorded first since they often involved pupils from Glasgow primary schools taking part in the programmes. These pupils were brought to the studios in large cars (which the pupils always seemed to think were Rolls Royces – unlikely unless the Lord Provost was feeling very magnanimous about his personal vehicle) and rewarded with a box of chocolates. The studio was adapted using a variety of sets – classroom, garden, French market and dining room among others.

An evaluation report on the first year of operation was commissioned from Professor W. H. Ewing of Ohio State University. He found that the city had many reasons to be proud of the accomplishments of the first year. Technical problems had been few, there was a steady improvement in production quality and staff competence and cohesiveness and a favourable acceptance of the service by teaching staff in schools.

A class watching a programme

By 1972, when the service was under the directorship of Miss MacNiven, following the retiral of Mr Beaton, the annual budget had risen to £250,000 (about £3.2M today). There were 2 studios, 2 distribution channels feeding 340 schools and colleges, 4 videotape recorders, 3 telecine chains, a still and cine film unit, a graphics department and a total of 950 receivers. Permanent staffing had increased to 36 with 50 part-time teachers for scripting and presenting programmes. There was a weekly schedule of some 100 transmissions, covering a wide variety of different subjects and levels: maths, history, science, health and hygiene, technical subjects, programmes for infants, modern languages, geography, religious education, commerce, speech and drama and programmes for the deaf. There were experiments in conjunction with Glasgow and Strathclyde Universities with adult education series on “The Changing Face of Glasgow” and “Biology”. The Service’s role in the in-service training of Glasgow teachers proved a very valuable one and was expanded through an ambitious 5 series of programmes from Jordanhill called “Television for Teachers”.

With the reorganisation of local government in 1975, Strathclyde Regional Council (SRC) assumed responsibility for education services and their associated budgets. At a time of financial stringency, SRC decided that their budget had to be cut by £17m out of a total of around £300M. Glasgow ETV was not excluded from these economies and SRC decided to close it down with an annual saving of £150,000 (less than the £230,000 saved by stopping school milk). This sparked a “Save Glasgow ETV” campaign with representations made to councillors, MPs, the unions and the STUC, trying to retain a “unique and valuable asset to Scottish education”. No doubt councillors from all over Strathclyde were unwilling to support a service that benefitted only Glasgow schools, even though the availability of domestic video cassette recorders (the Philips VCS was launched in 1972, Betamax in 1975 and VHS in 1976) would have provided the means of distributing Glasgow ETV programmes to the schools in the whole region. Money talked then as now and the service closed on 30th June 1976. The producers, scriptwriters and presenters went back to teaching. Many technical staff were transferred to the audio-visual service maintaining equipment in schools but there were inevitably some redundancies. The building at 155 Bath Street is now the home of an international IT and consultancy business.

And the legacy of Glasgow ETV? There are the teachers who were supported by the service through the hard work of adapting to the new syllabuses in Maths and the Sciences in the late 1960s and in the other subjects where rapid changes were the order of the day from then on. There are the Glasgow councillors and officials who had the foresight and courage to launch a service which attracted world-wide attention. And there are the pupils, many of whom hopefully are now fluent in French or can at least order a meal in a French restaurant with confidence and flair – most of them with vivid memories of their first attempts at spoken French guided by Madam Slack, Monsieur Patapouf and le chien Cliquot. Ecoutez et Repondez!

George Kirkland has been a physics teacher in Stirlingshire, Head of the Audio-Visual Media Department at Jordanhill College of Education, Director of Media Services at University of Glasgow and producer with his own interactive media company.

© George Kirkland 2015

(The photograph of the studio is from the collection at SCRAN. The other three are from an RCA company newsletter of March 1969.)